When I was eighteen, my dad invented something called “slack leashing.” Slack leashing is a sport involving one human, one dog, and a leash. You clip the leash on the dog like you’re going to go for a walk, but instead of the human setting the pace, you have to allow the dog to set the pace.

The ultimate goal of slack leashing is to never let the leash go taut. My dad developed all kinds of rules to go along with the sport: you had to drape the leash over your unclasped palm. You had to prance behind your dog. You had to go wherever your dog went, unless it was dangerous, in which case you shout “ALTAY” (I think a combination of “halt” and the Italian word for stop, “fine”), and redirect the dog. And, perhaps most hilariously, whenever your dog squatted to go to the bathroom, you also had to squat.

Soon, my 50 year old father was running all over our neighborhood after our energetic husky-mix. He’d gallop onto porches. Explore people’s backyards. Haphazardly zig zag across streets. All while prancing, one hand stretched flamboyantly outwards with the leash perched on it.

I still think slack leashing is a wonderful sport, and hope that it eventually catches on and becomes some new version of urban dogjoring.

But as a freshman in college–just getting the hang of life in the world without my parents–what was most apparent to me, was that slack leashing was a metaphor for how I’d been raised.

You see, both my parents have terminal degrees in child development and psychology, and their philosophies on child rearing are a far cry different from mainstream parenting. Commonplace practices like time out, being grounded, and having a curfew didn’t exist in my parents’ world.

I’ve always known that my parents had different rules than the parents of my friends (something that I felt vaguely smug about–my friends were always marveling at how crazy and cool my parents were).

But it wasn’t until I watched my dad careening around our neighborhood with Emma-the-dog that I realized those differences had been purposeful instead of haphazard. Powerfully purposeful.

My mom’s dissertation was all about a practice called “tripping” (which has nothing to do with drugs, I swear); a method of interacting with infants where you mimic their actions. Instead of trying to impose your own actions on them (doing something and seeing if they’ll copy it), you copy their actions.

So, for example, when L bangs on the table, I bang on the table too. Or when he shouts “AHHHHH,” I also shout “AHHHHH.” Many people do this naturally–it’s a way of interacting with infants that has been deeply woven into our DNA.

But the super cool thing about tripping is that it teaches really young infants that they have control over their surroundings. Babies are incredibly vulnerable. For the first months of their lives they’re unable to move their limbs on command, unable to navigate their environment.

By mimicking their movements and sounds, it gives them a small amount of power–and with power comes confidence.

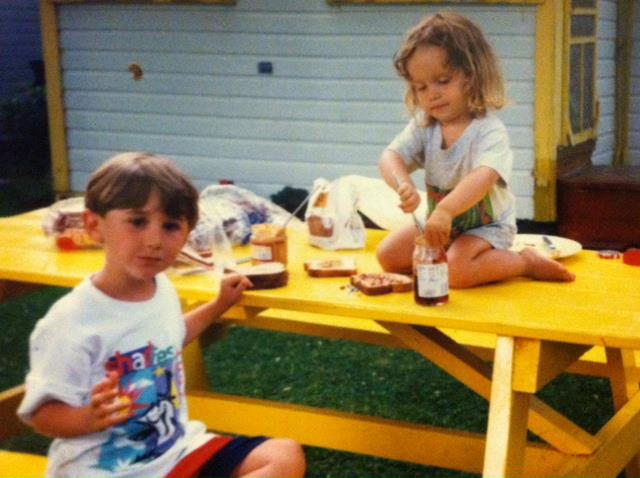

This pattern was mimicked throughout our lives. Whereas many parents are concerned with keeping their kids under control, my parents sought to give Jenna and I as much control as possible (while still also maintaining a routine–though that was so much fun Jenna and I didn’t even realize we were being guided through our day).

For example, during mealtimes, we each sat on a stool pulled up to the table. My parents goofed off and made us laugh while we all ate–and never said a word about what was on our plates. When I went off broccoli for a year (I somehow got it into my head that the teeny broccoli leaves looked like a cluster of spiders), my parents didn’t harass me about eating it. For the next meal, they just let me help pick which veggies I wanted to eat at the grocery store.

When I became a vegetarian in high school, they cooked vegetarian base meals, with meat on the side for the rest of the family.

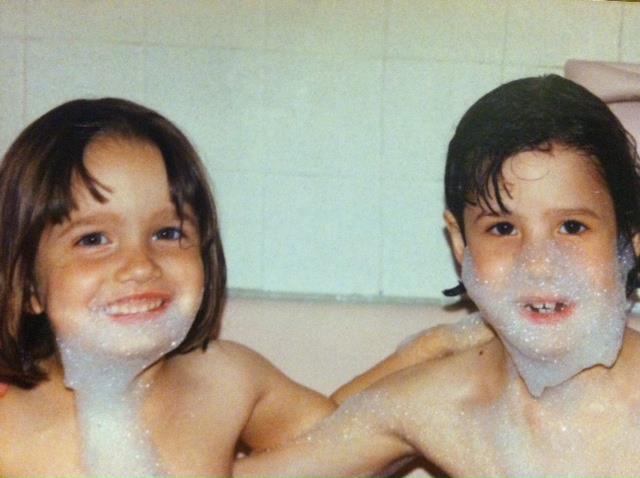

At bedtime, instead of telling us it was bedtime and that we needed to put our PJs on (a transition that can cause tantrums for many young kids), my dad simply told us to jump on to his back, to ride the giant ant up the stairs. He’d make weird “ant” noises (that sounded kind of like a giant kitten) and then bolt up the stairs, with one of us clinging to his back. Then he’d return for the other kid.

Going to bed is a lot more fun when a giant ant carries you to it.

Our toothbrushing routine was also a dance number–we’d dance and hop and wiggle while we brushed, and then my dad would encourage us to spit as big as we could.

Afterwards, we picked out our pajamas (instead of him giving us PJs to put on), and picked out which book we wanted to read.

They let us take risks on our own terms: jumping from couch to couch; climbing the walls; sitting in a laundry basket, hooking a dog to it and throwing a toy down the stairs; sliding down the banister; galloping around on horseback without a saddle or bridle; biking/scootering around the neighborhood without supervision; all of these were condoned activities in my world.

When we misbehaved or a situation started to get truly dangerous (which was rare–why misbehave when you’re given all the power, and life is so fun?), my parents employed the same tactic that my dad used while slackleashing: stop the behavior, and redirect.

In really serious instances, my mom and I would go for a drive alone, and she would talk to me about what kind of person I wanted to be. “You were acting like Angelica [from the Rugrats] when you wouldn’t share with your little sister. That kind of behavior is selfish. Do you want to be selfish, like Angelica?”

By comparing my actions to a character who I despised, she gave me context for my behavior. She made me realize how I came off to a third party, and gave me the incentive to change my own behavior.

Instead of punishing me or putting me in time out–in which case my motivation to change my behavior would’ve been to avoid a future punishment–my motivation to change was simply to be a better person.

I can’t imagine the amount of patience and energy this type of childrearing must have required on my parents’ part. And they definitely weren’t perfect–my mom lost her temper and chased me through the house more than once for some nefarious deed or another, and my mom and I were known for our shouting matches while I was in high school.

I also can’t comment on how I turned out as a human being–because well, I’m biased and imperfect, and who knows how I would’ve turned out in a different house, with different parents.

But I can attest to how wonderful it felt being parented like that.

It made being a teenager, and then now an adult, relatively simple. I formed my own beliefs and morals as a child, instead of adhering to beliefs and morals that were purposefully impressed upon me. (Which saved me the identity crisis that most teenagers go through).

Whereas many of my friends from more strict households went to college and became heavy drinkers or experimented with drugs and casual sex, I didn’t have any interest in participating in those things.

My parents had encouraged me to drink under their roof through high school–so that I could learn my limits in a safe environment–and my mom was constantly harping on about how I should “experience as many men as possible.”

Because my parents didn’t impose limits on me, I had to create my own limits for myself. And breaking limits that you’ve developed for yourself isn’t quite as fun as breaking the rules your parents have set for you.

Ultimately, I never had to question who I was outside of my parents. I knew, and I had confidence in who I was.

My greatest wish for L is that we can give him a childhood that is as wonderful as my own was–full of warmth and love and laughter. To give him that magical balance of support and power.

We’ve started early–letting him set the rhythm of his day, doing baby-led weaning (where you let your kid use their fingers to eat, instead of spoon-feeding), and mimicking his movements and sounds.

Since L was born, I’ve felt a little bit like I’m slack leashing. I’m trotting behind him–trying to keep the leash just loose enough that he never feels like he’s on one. So that one day, when we hand the leash over to L, he’ll know exactly how to lead himself.

What parenting strategies did your parents use with you? How do you think it’s shaped who you are today?

You have the best parents in the world. They were Always So good to Casey and Andy and the boys loved them so much!

I know you 2 will be wonderful parents too!

Thanks Pam! They’re pretty wonderful people. I hope we can live up to them!

You have the best parents in the world. They were Always So good to Casey and Andy and the boys loved them so much!

I know you 2 will be wonderful parents too!

Did mom really day “experience as many men as possible?” OMG. PS — I am available for private slack leashing lessons. What a wonderful post!!!

Yup, and that was the watered down version.

“Tripping” actually means T.R.I.P. which is Transactional Interaction Program; designed for children with special needs. Ellen helped develop the approach and based her dissertation on it at U of M with Gerald Mahoney and Amy Powell Wheatley. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gerald_Mahoney/publication/249833724_Modifying_Parent-Child_Interaction_Enhancing_the_Development_of_Handicapped_Children/links/54d4c7e90cf25013d029e70f/Modifying-Parent-Child-Interaction-Enhancing-the-Development-of-Handicapped-Children.pdf

Another wonderful piece from a wonderful new mother/adult raised by two wonderful (and intelligent) parents! Although one is a little “goofy”- only teasing Warren! Love all your writings- keep them coming! And love that Linden! ❤️

Thanks Kathie! They’re pretty wonderful. I have big shoes to fill in the parenting department, I’m not sure it’s possible to be as goofy as my dad 🙂

Just wonderful Sarah!!! Great insight and great writing. Thank you. (And you enjoyed you outing your dad a little more. )

Thanks so much for reading, Mark! I can never pass up a chance to write a blog post at my dad’s expense 🙂

Thank for sharing Sarah. I like the term and concept of “slackleashing” over an alternative approach that’s sometimes used in parenting circles, that being “free range”. As Mark said, great insight!

Ellen’s parents were like that, too. It was always the coolest house to hang out in through high school; Mel and Izzy were nonjudgmental and always there if any of us needed to talk. It’s wonderful to hear how she and Warren raised their own kids.

My grandparents are really amazing–they gave my mom gifts (generosity and nonjudgementalness and humor) that hopefully we can pass down through the generations. ❤